Bette Gardner looks back to the confluence of events that inspired her to create Friday Night at the ER in 1992, and offers insights into the game’s enduring relevance three decades later

Bette Gardner developed Friday Night at the ER to teach people about systems thinking, and how they can use systems thinking to make decisions and adjustments locally that align with system-wide performance goals.

I remember the moment of inspiration back in 1991. I was on a flight home, Boston to San Francisco, from a System Dynamics conference where I had played the tabletop simulation, The Manufacturing Game. I’d been toying with the idea of creating an experiential learning activity to meet a compelling need in my healthcare work, and playing this game was a catalyst.

Flying above the clouds at 35,000 feet, my mind drifted in reflective thought. The flight attendant interrupted, handing out beverages and snacks, and on that tiny napkin, I sketched what would become the Friday Night at the ER game board. Such a cliché, but this innovation truly first took shape on the back of a napkin. This was the moment that got me rolling. During the coming months, I would develop a team-learning game that would engage participants and a debrief that would generate valued learnings.

Stepping Back in Time

That was the physical origin of Friday Night at the ER, but its conceptual origin preceded that moment on the airplane.

Earlier in my career, I had been a researcher and policy analyst where I learned what did and didn’t work in U.S. healthcare. I had worked in healthcare system management and saw what it takes to manage patient care and population health. I had been a management consultant in a number of healthcare settings.

Problem solving within complex and dynamic systems requires an understanding of how the parts of the system are interrelated and change over time.

One day in 1988, a phone call from a colleague opened a new door. Mort Raphael of The San Francisco Foundation told me, “I’m sending you an article you have to read. It will change your life.” What he sent was the text of a speech delivered by Russell Ackoff, an operations research and systems thinking pioneer. It was my first exposure to the discipline of systems thinking and resonated deeply with what I knew to be true about making big, lasting change.

The idea – that problem solving within complex and dynamic systems required an understanding of how the parts of the system are interrelated and change over time, and that solutions depend on non-linear feedback relationships – was profoundly different than conventional problem-solving methods.

Mort was right! The Ackoff article inspired me to learn more. I read, attended conferences, experimented, and had the privilege of working with two exceptional systems scientists, Barry Richmond and Mark Paich, on projects in healthcare. I was on a path.

The Hospital Case that Became the Game Scenario

By 1990, I had become an advisor to a network of hospital leaders coming together to learn about integrating systems thinking and quality improvement. One of the network participants, San Jose Medical Center COO Bob Brueckner, came to me with a challenge. His hospital’s emergency department was frequently overwhelmed, and they often had to tell paramedics to bypass the hospital. “We need a new approach,” he said. “Smart people have been working on this, but they’re frustrated and they’ve started to blame each other.”

I took this case as a consulting engagement, and with a team of stakeholders, learned that the solution was well beyond the boundaries of the crowded emergency department. We studied patient flow throughout the hospital, building a computer-based simulation model to quickly test ideas and see consequences of many potential interventions – testing that would have been impossible in the real world.

Significantly, we learned that the hospital could dramatically improve performance in the ER and stop the diversion of paramedic patients with just three interventions that involved people from multiple departments of the hospital. It was a system problem that required a systems thinking solution.

This case would later become the scenario for Friday Night at the ER.

An Emerging Market and a Drive for Widespread Change

In the early 1990s, Peter Senge’s influential book, The Fifth Discipline, became a best seller among organization leaders. Accessible and readable, it positioned systems thinking and related disciplines as key to organizational learning and transformative change. The buzz around these concepts was palpable and moved many people to think differently.

Two questions were on my mind at that time. First, would these ideas trickle down and spread to everyday people in organizations and in communities? That seemed essential to achieve the transformative benefit. Second, how would believers put these ideas into practice in their work? In other words, what would applied systems thinking look like?

I came to believe that an experiential learning activity was needed. It would be learning by doing — a practice field for working within a complex, dynamic system and getting desired results. Success in the exercise would require the actions and behaviors of applied systems thinking.

A Game is Born

How does one make a learning experience suitable for a wide range of people? I drew from my experience with simulation as a powerful learning technique. I drew from my work experience and the case of the hospital that was turning away paramedic patients. I was inspired by an example of a tabletop team-learning game.

The game experience teaches that individual departments working toward their own separate objectives are not effective. Excellent performance is only achieved by collaborative efforts involving the entire system.

One challenge was honing the game-play scenario and core teachings to produce a focused and clear set of practical lessons. The game play and debrief had to fit within three to four hours for widespread use.

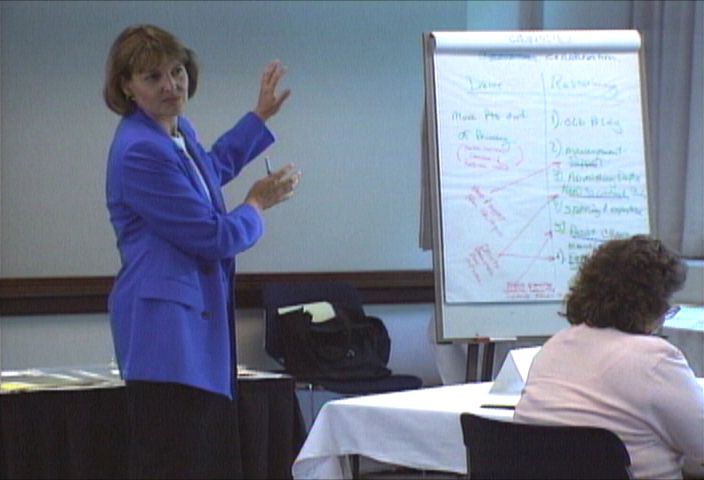

I designed Friday Night at the ER as a board game that simulates the challenge of managing a hospital during a 24-hour period. To keep the game activity to just one actual hour, the game board compresses the hospital into just four departments, and virtual hours tick by in minutes.

Four players per game board each play the role of a hospital department manager, each handling patient flow and staffing, dealing with situations that arise and documenting performance. Patients and staff arrive and depart, workloads are uneven, events pop up unexpectedly, department managers communicate, scores accumulate.

Players each perform distinct functions, yet they come to realize they also depend on each other. They discover that quality and cost problems can be solved only if they collaborate, if they are open to new ideas, and if they use data for decision-making – three essential behaviors for putting systems thinking into practice.

From Makeshift Beginnings to a Professional Product

The learning process begins as soon as players realize that they must reach across functional boundaries and work as a team to achieve quality and cost goals.

The first test of the game play took place at my dining room table with four willing friends. The game board was brown paper on which I had drawn blocks and chutes to represent hospital departments and corridors. Among the game parts were hospital staff (raw garbanzo beans) that would care for patients (macaroni noodles). I explained the game instructions and observed, notepad in hand, what happened.

Dubious at first, these testers became thoroughly engaged as if they were actually managing departments of a hospital. They were challenged by spikes of demand, they worried about their patients getting into care, they were cautious with spending, they were busy with their own responsibilities…until a certain pressure point. During the hectic Friday night hours, they began to come up with ideas for change. They reached across department boundaries on the game board to share resources and new ideas. They had moved from silo thinking to systems thinking. It worked!

The handmade materials went to a professional designer, and I then started using the game in my work with clients. Repeatedly I was verifying that the game play was dynamic, sometimes competitive, often fun, always rich with learnings. “It’s frighteningly real,” said one hospital CEO. “A powerful learning experience,” said a night-shift nurse supervisor. “This is our company!” exclaimed a manufacturing manager.

The rest of the development process is a longer story. It included creative design, computer-based simulation modeling, curriculum design, user testing, materials sourcing, refinements and finally, manufacturing.

In 2014, the game received a comprehensive update — from the graphics on the game board, to the modular packing system, to the extensive facilitator support materials (including an online certification course).

Let’s Not Forget About the Debrief

The initial learning value of Friday Night at the ER occurs during the game play as players realize what it takes to be successful. The rest takes place during a structured debrief, when participants are guided to reflect about the experience, share insights and apply them to their work.

The learning capstone is the debrief when players are guided to examine their assumptions and learn why and how their performance was self-limiting. They must step back from the flurry of action (the game play) to reflect about the lessons of the experience and their practical application.

With the group size usually ranging from 12 to 60 participants (using 3 to 15 game boards) or more, we post game scores that measure each team’s performance in hospital quality and cost. During the stretch break that follows the game play, people peruse and compare team scores – a motivating lead-in to the debrief to learn how and why the best-scoring teams achieved their results.

The structured debrief that I created and packaged with the game kit combines reflection, dialogue, presentation, exercises and actionable steps.

Widespread Use 30 Years and Counting

During its 30-year history, the hands-on experience and lessons of Friday Night at the ER have found relevance and diverse use within healthcare and beyond. Today it is used by people teaching a range of improvement disciplines including Lean, Agile and Six Sigma.

In The Netherlands, for example, organizational change advisor Linda van der Steen uses the game in her work helping small government agencies develop self-organizing teams to respond more effectively to major transitions such as municipal mergers.

“Friday Night at the ER offers organizations the opportunity to focus on important organizational topics and gain refreshing insights,” Linda says. “The players are cut off from their daily practice so that they are open to the conversation and can think freely. This experiential learning method offers lessons and insights that players can put into practice daily.”

Many hospitals use the game to improve patient flow and reduce ED crowding. Others use it to teach interdisciplinary teamwork and coordination within systems of care.

At the Harrison School of Pharmacy at Auburn University, the game is an ideal way for students to experience both the importance of effective teamwork and the challenges they may face with interprofessional collaboration in their future roles.

“We discuss the concepts of collaboration, innovation, data-driven decision making, and structure driving function. Each of these principles translates to interprofessional practice well,” explains Clinical Assistant Professor Jeanna Sewell.

The Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality uses Friday Night at the ER for executive learning within the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

“We use the game to teach soft leadership skills like communication and collaboration to future Navy Medicine leaders,” explains Melinda Sawyer, Director of Patient Safety and Education. “The simulation and debrief help them identify and remove barriers for operating with cost efficiency and high levels of quality and patient safety.”

The game is a unique and engaging learning experience that is relevant across cultures and industries.

People in all industries and cultures relate Friday Night at the ER to their own challenges. CEO Mark Jin of the Human Resource Excellence Center, China’s largest network for HR professionals, says, “Friday Night at the ER is a powerful learning experience that delivers key lessons in cross-functional collaboration for our clients, many of which are China-based Fortune 500 and Forbes 2000 companies.”

Friday Night at the ER has found relevance in companies in all industries, in academic settings, community groups, government agencies, and nonprofits. It works for everyone because the hospital is a familiar setting to everyone and lessons of the game are universal. Systems thinking is timeless, as relevant today as it was 30 years ago.